Giant Virus Discovered in Japanese Pond May Hint at Multicellular Life’s Origins : ScienceAlert

In a groundbreaking discovery that’s sending shockwaves through the virology community, scientists in Japan have identified a colossal new virus lurking in the waters of a tranquil pond near Tokyo. The newly discovered “ushikuvirus” not only expands our understanding of giant viruses but may also hold the key to one of biology’s most profound mysteries: the evolutionary leap from simple single-celled organisms to complex multicellular life.

The virus was found infecting amoebae in Ushiku-numa, a freshwater pond in Ibaraki Prefecture, and its discovery represents a significant milestone in our ongoing quest to understand these enigmatic biological entities that straddle the line between living and non-living matter.

The Hidden World of Giant Viruses

For decades, giant viruses remained hidden in plain sight. These massive infectious agents were so large that when first discovered, researchers often mistook them for bacteria. It wasn’t until recent decades that we began to appreciate just how prevalent and important these microscopic giants truly are.

Today, we know that viruses constitute the most abundant biological entities on Earth, with some estimates suggesting there are more viruses in a single liter of seawater than there are people on the entire planet. Yet despite their ubiquity, viruses remain among the most mysterious forms of life—or near-life—on our planet.

The question of whether viruses are truly “alive” continues to spark intense debate in the scientific community. Unlike bacteria, viruses cannot reproduce independently; they require host cells to replicate. They lack many of the characteristics we typically associate with living organisms, yet they possess genetic material and evolve over time, displaying behaviors that suggest a form of biological intelligence.

Viruses: The Invisible Architects of Evolution

What makes viruses particularly fascinating is their profound influence on the evolution of all life forms, including humans. Far from being mere pathogens, viruses have played a crucial role in shaping the genetic landscape of every organism on Earth.

One of the most remarkable aspects of viral biology is their ability to facilitate horizontal gene transfer—the movement of genetic material between organisms outside of traditional reproduction. This process has been instrumental in driving evolution, allowing organisms to acquire beneficial traits from entirely different species.

Perhaps even more astonishing is the revelation that ancient viral DNA now comprises up to 8 percent of the human genome. These endogenous retroviruses, remnants of infections that occurred millions of years ago, have left an indelible mark on our genetic code.

Some of these viral remnants have proven surprisingly beneficial. Retroviral DNA may have enabled early vertebrates to develop myelin, the insulating sheath that allows for rapid nerve conduction. More significantly, viral genes were crucial in the evolution of the placenta, a defining feature of mammalian reproduction.

The Viral Eukaryogenesis Hypothesis: A Radical Theory of Life’s Origins

The discovery of ushikuvirus comes at a time when scientists are grappling with one of biology’s most fundamental questions: how did complex eukaryotic cells—the building blocks of all multicellular life, including humans—evolve from simpler prokaryotic cells?

This evolutionary transition represents what researchers describe as a “chasm in design.” Prokaryotic cells, like bacteria, lack membrane-bound organelles and have relatively simple internal structures. Eukaryotic cells, by contrast, possess complex internal architecture, including a nucleus that houses genetic material.

The mechanism behind this dramatic evolutionary leap has long puzzled scientists. Enter the viral eukaryogenesis hypothesis, a revolutionary theory first proposed by Masaharu Takemura, a molecular biologist at Tokyo University of Science, in 2001.

Takemura’s hypothesis suggests that the nucleus of eukaryotic cells may have originated from a large DNA virus, similar to modern poxviruses, that infected a prehistoric prokaryotic cell. Rather than destroying its host, this ancient virus established a symbiotic relationship, gradually evolving into what we now recognize as the cellular nucleus.

This theory gained significant support with the 2003 discovery of giant viruses containing DNA that form structures called “virus factories” inside host cells. These factories, sometimes enclosed in membranes, bear striking similarities to eukaryotic nuclei in both structure and function.

Ushikuvirus: A New Piece in the Evolutionary Puzzle

The ushikuvirus discovery provides compelling new evidence supporting the viral eukaryogenesis hypothesis. This massive virus, measuring significantly larger than typical viruses, infects amoebae of the species Vermamoeba vermiformis—the same hosts targeted by clandestinoviruses.

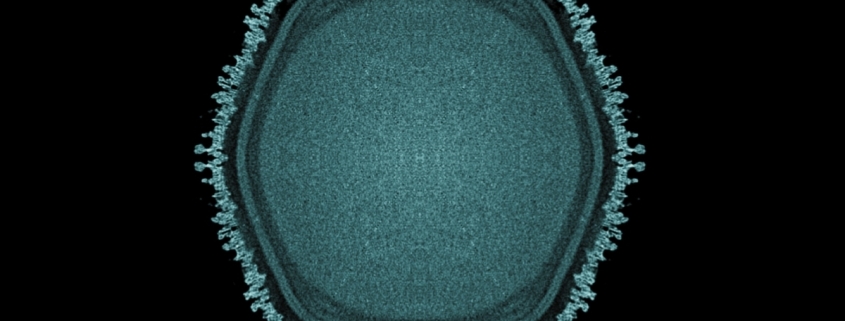

What makes ushikuvirus particularly intriguing is its unique combination of features. While it shares the spiky capsid surface and overall shape of medusaviruses, it exhibits distinctive characteristics that set it apart from other giant viruses.

Most notably, ushikuvirus forces its host cells to grow abnormally large—a behavior that mirrors the cellular changes observed during early eukaryotic evolution. Additionally, its capsid spikes possess unique caps and fibrous structures not seen in other giant viruses.

Unlike some of its relatives that preserve host cell nuclei during replication, ushikuvirus takes a more aggressive approach, forming viral factories and destroying the host’s nuclear membrane. This destructive behavior, paradoxically, may provide insights into how viral infection could have led to the development of more sophisticated cellular structures.

Implications for Understanding Life’s Origins

The discovery of ushikuvirus represents far more than just the identification of another virus species. It provides scientists with a living model for understanding the complex interactions between viruses and their hosts that may have shaped the course of evolution billions of years ago.

As Takemura explains, giant viruses represent “a treasure trove whose world has yet to be fully understood.” The study of these massive infectious agents could ultimately provide humanity with a new perspective on the relationship between living organisms and viruses—a relationship that has been fundamental to the development of life as we know it.

The ushikuvirus discovery is expected to stimulate important discussions about the evolution and phylogeny of the Mamonoviridae family and related viruses. By comparing the characteristics of different giant viruses, scientists hope to reconstruct the evolutionary pathways that led to the incredible diversity we see today.

The Future of Viral Research

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond academic curiosity. Understanding the evolutionary history of giant viruses could have practical applications in fields ranging from medicine to biotechnology.

As researchers continue to uncover the secrets of these massive viruses, they may discover new tools for genetic engineering, novel approaches to treating viral infections, or even insights into the potential for life on other planets.

The study of ushikuvirus and its relatives represents a frontier in scientific research, one that promises to reshape our understanding of life’s origins and the fundamental processes that drive evolution.

Tags: giant virus discovery, ushikuvirus, viral eukaryogenesis, evolution of life, Tokyo University of Science, Masaharu Takemura, amoebae infection, viral origins, cellular evolution, microbiology breakthrough, freshwater pond research, giant virus family, Mamonoviridae, viral gene transfer, endogenous retroviruses, eukaryotic evolution, prokaryotic to eukaryotic transition, virus factories, capsid structure, genetic engineering tools

Viral Phrases: “treasure trove of viral secrets,” “giant viruses hiding in plain sight,” “8% of human DNA from ancient viruses,” “viruses that shaped our very existence,” “the invisible architects of evolution,” “a new view connecting life and viruses,” “reshaping our understanding of life’s origins,” “the viral eukaryogenesis revolution,” “giant viruses: the missing link?” “from pond water to evolutionary breakthrough,” “viruses that built the first nucleus,” “the 25-year quest to understand viral origins,” “how a virus infection created complex life,” “the cellular revolution sparked by infection,” “unlocking the mysteries of the viral world”

This discovery reminds us that some of the most profound scientific breakthroughs can come from the most unexpected places—in this case, a quiet pond near Tokyo. As we continue to explore the viral world, we may find that these tiny giants hold the answers to some of our biggest questions about life itself.

,

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!