Expired Cans of Salmon From Decades Ago Preserved a Huge Surprise : ScienceAlert

Ancient Canned Salmon Reveals Decades of Alaskan Marine Ecology

In a remarkable twist of scientific serendipity, researchers have uncovered a hidden archive of Alaskan marine ecology preserved in the most unexpected place: decades-old canned salmon sitting in the back of a Seattle warehouse.

When Seattle’s Seafood Products Association reached out to University of Washington ecologists Natalie Mastick and Chelsea Wood about taking boxes of dusty, expired canned salmon off their hands—some dating back to the 1970s—they couldn’t have anticipated the ecological treasure trove they were offering.

What began as a simple request to clear storage space transformed into a groundbreaking study that would reveal decades of marine ecosystem health through the lens of tiny, preserved parasites.

The Unexpected Archive

The canned salmon collection represented more than just forgotten food products. Each can served as a time capsule, preserving not only the fish but also the marine parasites that had inhabited them decades earlier. This accidental natural history museum offered researchers an unprecedented opportunity to track changes in Alaskan marine ecosystems over a 42-year period from 1979 to 2021.

The collection included 178 cans containing four different salmon species: 42 cans of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), 22 coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch), 62 pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), and 52 sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka), all caught in the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay.

Parasites as Ecosystem Indicators

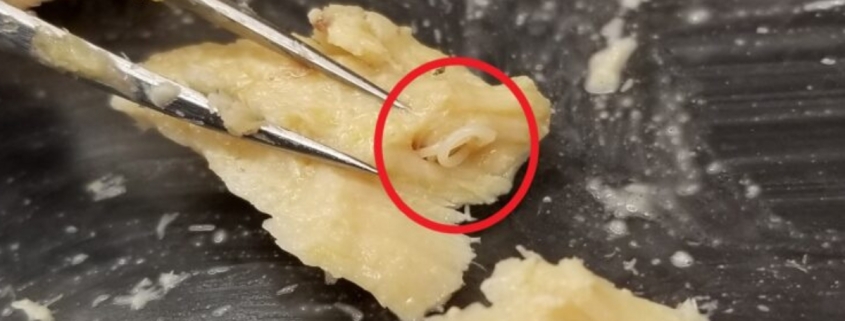

Marine parasites, particularly anisakid worms, serve as remarkable indicators of ecosystem health. These roughly 0.4-inch (1-centimeter) long nematodes enter the food web when consumed by krill, which are then eaten by larger species like salmon. The worms eventually make their way to marine mammals, where they complete their life cycle by reproducing, with their eggs returning to the ocean to begin the cycle anew.

As Chelsea Wood explains, “Everyone assumes that worms in your salmon is a sign that things have gone awry. But the anisakid life cycle integrates many components of the food web. I see their presence as a signal that the fish on your plate came from a healthy ecosystem.”

The presence of these parasites indicates a functioning, complex food web with sufficient hosts to support their life cycle. If marine mammals—the final hosts for anisakids—are absent from an ecosystem, the parasites cannot complete their reproductive cycle, and their numbers would decline.

Laboratory Analysis and Findings

The research team meticulously dissected salmon fillets from each can, calculating the number of worms per gram of salmon tissue. Despite the canning process degrading the worms’ physical condition, the researchers were able to gather valuable data about parasite abundance over time.

Their analysis revealed fascinating patterns: worm counts increased over time in chum and pink salmon, but remained stable in sockeye and coho. This differential pattern suggests varying ecosystem dynamics affecting different salmon species.

Natalie Mastick noted, “Seeing their numbers rise over time, as we did with pink and chum salmon, indicates that these parasites were able to find all the right hosts and reproduce. That could indicate a stable or recovering ecosystem, with enough of the right hosts for anisakids.”

The Complexity of Marine Ecosystems

The stable worm levels in coho and sockeye salmon present an intriguing puzzle. The canning process made it difficult to identify specific anisakid species, limiting the researchers’ ability to draw definitive conclusions about why these particular salmon species showed different patterns.

As the research team wrote in their published paper, “Though we are confident in our identification to the family level, we could not identify the [anisakids] we detected at the species level. So it is possible that parasites of an increasing species tend to infect pink and chum salmon, while parasites of a stable species tend to infect coho and sockeye.”

This uncertainty highlights the complexity of marine ecosystems and the intricate relationships between parasites, their hosts, and environmental factors.

Implications for Marine Conservation

This innovative research demonstrates the value of thinking creatively about scientific data sources. What many would consider worthless expired food products became a valuable ecological archive, providing insights into marine ecosystem health over four decades.

The findings suggest that certain Alaskan salmon populations may be thriving within healthy, functioning ecosystems, as evidenced by the increasing parasite loads in chum and pink salmon. This information proves invaluable for marine conservation efforts and fisheries management.

The Future of Ecological Research

Mastick and Wood believe this novel approach—repurposing archived materials for ecological research—could fuel many more scientific discoveries. Their work opens new possibilities for using existing collections and archived materials to study long-term ecological changes.

As Wood aptly summarized their accidental discovery, they had indeed “opened quite a can of worms”—though in this case, those worms provided crucial insights into the health of Alaska’s marine ecosystems.

This research, published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, represents a creative leap in ecological methodology, demonstrating how scientific innovation often comes from unexpected sources and unconventional thinking.

The study serves as a reminder that valuable scientific data can be found in the most unlikely places, and that sometimes, the key to understanding our present and future lies in examining what we’ve left behind in our past.

Tags

parasite ecology, marine conservation, canned salmon, Alaskan ecosystems, University of Washington research, marine parasites, food web dynamics, ecological archives, fisheries management, environmental science, marine biology, ecosystem health indicators, anisakid worms, salmon populations, scientific innovation

Viral Sentences

- Scientists discover decades of marine ecology preserved in expired canned salmon

- Ancient parasites reveal secrets about Alaska’s ocean health

- Dusty old cans become treasure trove for marine researchers

- Worms in your salmon might actually mean your fish came from a healthy ecosystem

- Accidental natural history museum found in Seattle warehouse

- Parasites as the ultimate ecosystem health indicators

- 42-year-old canned fish provides unprecedented ecological data

- How expired food became valuable scientific research material

- Marine parasites tell the story of ocean ecosystem recovery

- The unexpected scientific value of forgotten canned goods

- When trash becomes treasure: expired salmon reveals ocean secrets

- Creative science: using old cans to track ecosystem changes

- Parasites in canned fish: gross or scientifically valuable?

- Marine ecology research gets a boost from pantry archaeology

- How worms became the key to understanding ocean health

- The surprising connection between parasites and ecosystem stability

- From storage room to science lab: the canned salmon revolution

- Why scientists are excited about finding worms in old fish

- The innovative approach that’s changing how we study marine ecosystems

- How expired food products became crucial ecological data sources

,

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!