In 1983, Bill Gates turned away from AI hype and championed “softer software” that adapted to users’ needs

AI’s Promise and Peril: Lessons from 1985’s Tech Revolution

In 2026, artificial intelligence permeates every facet of technology—writing code, generating images, composing audio and video, analyzing contracts, and managing customer support operations. Tech giants compete fiercely over model parameters and training datasets with the same fervor that automakers once showcased horsepower figures. Startups promise autonomous agents capable of running entire businesses independently. Regulators express mounting concerns about safety implications, while workers grapple with questions about their professional relevance in an AI-driven landscape.

Yet remarkably, as early as 1985—at the dawn of the personal computer revolution—some of the technology industry’s most perceptive observers were already cautioning that AI might become “the most despised and abused [software concept] of the next year.”

The Prophetic Warning from Mitch Kapor

This prescient observation emerged from Mitch Kapor, then-chairman of Lotus Development, during his address at the January 1985 Personal Computer Forum. Kapor’s warning captured a fundamental tension that continues to define our relationship with artificial intelligence decades later.

“The next big lemming-like rush will be to artificial intelligence,” Kapor predicted. “So in a perverse way, AI is an exciting opportunity for people who recognize what it can do for customers.”

His insight revealed an uncomfortable truth: technological revolutions often attract both genuine innovation and opportunistic exploitation. The companies that would ultimately succeed weren’t those making the loudest promises, but those delivering tangible value to users.

InfoWorld’s Prescient Editorial

The February 25, 1985 editorial in InfoWorld, titled “Awaiting AI Hype, Promise,” reads with astonishing relevance to our current technological moment. James E. Fawcette, the magazine’s Editorial Director and Associate Publisher, posed a question that could have been written yesterday: “Will 1985 be the year when artificial intelligence finally emerges from the ivory towers of academia to become a useful tool?”

Fawcette identified a critical challenge that remains unresolved: “Software companies desperate for new hooks to lure jaded users tired of the parade of me-too spreadsheets and word processors see artificial intelligence, or AI, as a possible savior.”

The parallels to 2023’s generative AI explosion are striking. The same desperation for differentiation, the same rush to rebrand existing technologies as revolutionary, and the same gap between marketing promises and practical reality.

The Terminology Problem

One of Fawcette’s most insightful observations concerned the very language we use to discuss artificial intelligence. “The problem is: What can AI really do? Even the words artificial intelligence are a barrier to the technology’s application. They are so value- and image-laden that the term itself obstructs practical work.”

This linguistic challenge persists today. The phrase “artificial intelligence” evokes visions of thinking machines, autonomous decision-makers, and science fiction scenarios that bear little resemblance to current technological capabilities. Fawcette warned that AI conjured “thinking machines, complete with Big Brother images of computers controlling our lives or making decisions for us.”

The terminology problem extends beyond mere semantics. When users expect human-like intelligence from software systems, disappointment becomes inevitable. The gap between expectation and reality creates a cycle of hype and disillusionment that has characterized AI’s evolution for decades.

Two Varieties of AI Abuse

Fawcette identified two distinct forms of AI misuse that remain painfully relevant in 2026:

AI-hype: “Vacuous programs that promise to make decisions for the user. Simply type in a handful of facts, and the program will run your business for you, tell you what stocks to buy, let you manipulate people.”

Rube Goldberg overdesign syndrome: “Overengineered systems built to solve grand problems rather than practical ones.”

These categories capture the dual nature of technological exploitation. The first involves empty promises and magical thinking—software that claims to solve complex problems through simple inputs. The second represents architectural hubris—systems designed to address theoretical challenges rather than real user needs.

If you’ve scrolled through LinkedIn recently, you’ve encountered both phenomena. AI-hype manifests in exaggerated claims about autonomous business operations and decision-making capabilities. Rube Goldberg syndrome appears in unnecessarily complex systems that solve problems nobody actually has.

The Microsoft Alternative: “Softer Software”

In response to AI’s problematic connotations, some technology evangelists began avoiding AI terminology entirely. “Given the damage these two schools of thought will cause, it is not surprising that some personal computing evangelists are avoiding AI terminology entirely,” Fawcette observed.

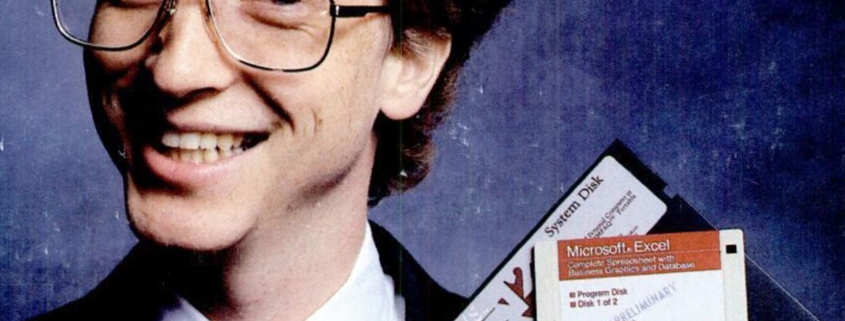

Microsoft’s Bill Gates emerged as a leading voice for this alternative approach. He coined the term “softer software” to describe his vision of programs that would learn users’ work patterns and assist in executing them. This rebranding effort represented a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize human-computer interaction.

Gates and Simonyi’s Vision

Two years before the InfoWorld editorial, in an August 29, 1983 piece, Bill Gates and Charles Simonyi discussed their alternative vision for intelligent software. “AI is a very complex goal,” Simonyi acknowledged. “You need a philosopher to determine what AI is.”

Rather than pursuing artificial intelligence as traditionally conceived, they proposed “softer software” as a more achievable and practical goal. This approach emphasized empirical learning and adaptation rather than abstract notions of machine intelligence.

“It modifies its behavior over time, based on its experience with the user,” Simonyi explained, “with the aim to make life easier for users in the real world.”

The Legacy of Charles Simonyi

Charles Simonyi, the legendary software architect who led the teams that created Microsoft Word and Excel, brought a pragmatic engineering perspective to the challenge of intelligent software. His influence extends far beyond these applications—if you’ve ever used a “pull-down menu,” clicked an “icon,” or worked with a “WYSIWYG” (What You See Is What You Get) editor, you’re experiencing his legacy.

Simonyi’s description of “softer software” anticipated many features we now consider standard in modern applications. “With softer software,” InfoWorld reported, “the program might ‘remember’ that whenever you request double-spacing, you also want right-margin justification and a particular heading on each page. The program has learned this by observing your habits.”

He predicted a future where computers would function as “working partners” that anticipate user behavior, suggest relevant actions, and adapt to individual preferences over time. This vision of adaptive, learning software has become reality in today’s personalization engines and AI assistants.

The Empirical Approach

Simonyi’s approach to “softer software” was fundamentally empirical rather than philosophical. Instead of attempting to replicate human intelligence, the goal was to create systems that learned from observation and experience.

“It will mold itself based on events that have taken place over a period of time,” he predicted. This user-centric approach focused on practical utility rather than abstract intelligence metrics.

We can recognize this philosophy in contemporary software and AI assistants. Modern applications learn from user interactions, adapt to preferences, and provide increasingly personalized experiences. The difference lies in scale and sophistication—today’s systems process vastly more data and employ more advanced algorithms, but the fundamental principle remains unchanged.

Microsoft’s First Steps: Expert Systems

While these ideas sounded futuristic in 1983, Microsoft had already begun implementing them. “While such descriptions sound futuristic,” InfoWorld noted, “Microsoft has taken the first tentative steps toward what Gates and Simonyi believe will be the application of the softer-software dream. They call the packages ‘expert systems.'”

The initial focus was on improving Microsoft’s spreadsheet program, Multiplan. Rather than presenting users with empty cells requiring manual formula creation, these expert systems could build formulas, create categories, and analyze data automatically.

This approach represented a significant departure from traditional software design. Instead of requiring users to master complex syntax and procedures, the software would learn from user behavior and provide intelligent assistance.

The Evolution to Excel

Multiplan would eventually be succeeded by Excel, Microsoft’s next-generation spreadsheet software that would go on to dominate the market for decades. The May 27, 1985 issue of InfoWorld reviewed the first version of Excel for the Macintosh (Windows 1.0 wouldn’t arrive until later that year).

Reviewer Amanda Hixson highlighted Excel’s “learn-by-example macro feature” as “the first step toward software that satisfies the promise of ‘softer software,’ as Bill Gates described his dream of a coming generation of products geared to make computer use as easy as possible and still provide maximum performance.”

Excel’s macro system allowed users to record their actions and replay them later, creating automated workflows without requiring programming knowledge. “You could type them in…or use Excel’s learn-by-example method,” Hixson explained, “where ‘Excel will remember what you do on a worksheet, write macro code as you do it, then let you rerun what you’ve done by calling the macro.’ You didn’t need to understand programming ‘to create powerful Excel macros.'”

This approach democratized automation, making powerful functionality accessible to non-technical users.

Competing Philosophies: Excel vs. Lotus Jazz

At the time, Lotus 1-2-3 dominated the spreadsheet market, but Gates criticized the philosophy behind Lotus Jazz, the company’s new all-in-one software suite. “We don’t believe in the Jazz philosophy… which is to take all your uses — words, numbers, database… and spread them in five different directions. So there is significant compromise.”

Microsoft’s approach, Gates argued, was “to take these three areas and do appropriate integration within each area.” This philosophy of focused excellence over broad but shallow functionality would characterize Microsoft’s strategy for years to come.

Excel ultimately outlasted Jazz not through revolutionary promises but through consistent delivery of practical value. As Hixson wrote, Excel succeeded through “consistency, power, lots of features, and macros.”

The Copilot Philosophy

Throughout this evolution, Gates maintained a consistent philosophy: software should function as a copilot rather than an oracle. Rather than positioning software as an all-knowing decision-maker, the goal was to create intelligent assistants that enhanced human capabilities.

This copilot approach represents a crucial distinction that remains relevant in 2026. Modern AI systems that position themselves as partners and assistants tend to find greater acceptance than those that claim to replace human judgment entirely.

The 1985 Vision Realized

The 1985 InfoWorld editorial imagined software capable of generating sales reports “but this time throw in a bar chart of the European market.” What once sounded speculative now feels routine. AI systems routinely draft quarterly reports, summarize meetings in real time, and generate visualizations from simple text descriptions.

These systems operate as “agents,” executing multi-step tasks across applications and platforms. The vision of intelligent software that anticipates needs and provides proactive assistance has largely been realized, though perhaps not in the exact form envisioned in 1985.

The Enduring Challenge

The same editorial included a line that remains profoundly relevant: “We’ll get our first taste [of AI] this year. Let’s hope some applications are as intelligent as the software algorithms used to implement them.”

This observation captures a persistent challenge in AI development: the gap between algorithmic sophistication and practical utility. Advanced algorithms may perform impressively in controlled environments but fail to deliver meaningful value in real-world applications.

Bill Gates didn’t reject intelligence in software; rather, he rejected the mythology surrounding it. By talking about “softer software,” he envisioned systems that learned from users, adapted to context, and acted as partners—copilots rather than all-knowing oracles.

The Cycle Continues

The technology industry has cycled through periods of AI enthusiasm and disillusionment repeatedly since 1985. Each wave brings new promises, new disappointments, and new opportunities for genuine innovation.

The fundamental challenge remains unchanged: how to create software that genuinely enhances human capabilities without overpromising or underdelivering. The companies that succeed are those that focus on practical utility rather than abstract intelligence.

Tags and Viral Phrases

- AI hype cycle repeats every decade

- Bill Gates predicted AI assistants in 1983

- Excel macros were the first AI automation

- Software should be a copilot, not an oracle

- The terminology problem: why “AI” creates unrealistic expectations

- Charles Simonyi invented the pull-down menu and WYSIWYG

- Microsoft’s “softer software” philosophy from 1983

- AI abuse: hype vs. overengineering

- The gap between algorithmic sophistication and practical utility

- Why AI keeps disappointing and then surprising us

- The enduring wisdom of 1985 tech predictions

- How Microsoft avoided the AI hype trap

- The real meaning of “intelligent software”

- Why “softer software” beats “artificial intelligence”

- The copilot philosophy that conquered the tech world

- Excel’s learn-by-example macros predicted modern AI

- The Rube Goldberg overdesign syndrome in modern AI

- Why terminology matters more than technology

- The practical path to useful AI assistants

- How Bill Gates saw through the AI hype in 1985

- The user-centric approach to intelligent software

- Why Microsoft’s approach to AI still works today

- The enduring challenge of expectation vs. reality in AI

- How 1985’s tech wisdom applies to 2026’s AI revolution

,

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!