NIH head, still angry about COVID, wants a second scientific revolution

MAHA Institute Event Highlights Growing Rift Between Science and Political Ideology

The recent MAHA Institute gathering has exposed a widening chasm between traditional scientific institutions and a politically energized faction of “ordinary Americans” seeking to reshape how science is conducted in the United States. What unfolded was less a discussion about improving research methodologies and more a manifesto for what organizers termed the “second scientific revolution.”

The event, which drew supporters of the Make America Healthy Again movement, featured a series of presentations that blended legitimate scientific concerns with alternative health narratives and political grievances. The atmosphere was charged with frustration over pandemic-era policies, with speakers and audience members alike expressing deep skepticism toward established scientific authorities.

One of the most striking moments came when an audience member questioned why alternative treatments weren’t receiving more research attention, while another speaker proudly announced his family had never received COVID-19 vaccines—a declaration that earned enthusiastic applause. The afternoon’s programming included a fifteen-minute segment devoted to a novelist seeking funding for a satirical pandemic film portraying Dr. Anthony Fauci as an “egomaniacal lightweight” and depicting vaccines as essentially placebos.

The organizers appeared acutely aware that their event might face critical scrutiny from mainstream scientific media. Reporters from both Nature and Science were denied entry, suggesting a deliberate effort to control the narrative and avoid challenging questions from established scientific journalism outlets.

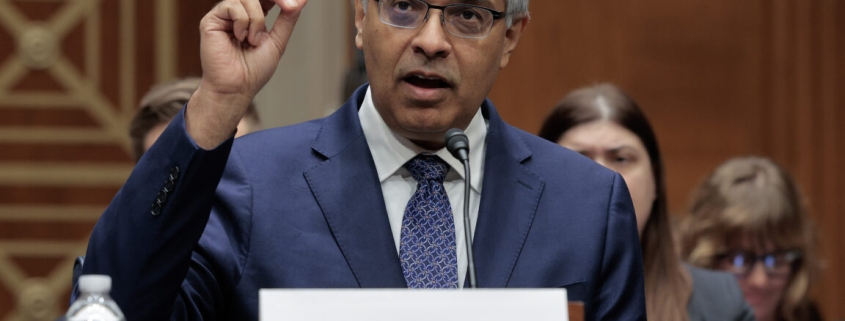

At the center of the proceedings stood Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, who positioned himself not merely as an administrator implementing changes at the National Institutes of Health, but as the architect of an entirely new scientific paradigm. His vision, which he termed the “second scientific revolution,” drew parallels to the first scientific revolution that shifted authority from ecclesiastical institutions to empirical observation.

Bhattacharya’s framework emphasized what he called the “replication revolution,” arguing that scientific success should be measured not by publication counts but by whether independent researchers can reproduce findings. He contended that the COVID-19 crisis revealed how “high scientific authority” had overstepped its bounds, not just in determining physical truths but in dictating moral and social behaviors—such as treating neighbors as “mere biohazards.”

The intellectual disconnect at the heart of the event was striking. Attendees expressed anger over pandemic policies, mask mandates, and vaccine requirements, yet the proposed solutions focused on methodological reforms like replication standards and publication metrics. There was little direct connection between the grievances aired and the institutional changes being advocated.

This disconnect, however, appears to be precisely what makes the MAHA movement politically potent. The coalition brings together individuals united by shared frustration with establishment science, regardless of whether their specific concerns align with the proposed reforms. The movement has tapped into a powerful constituency that feels alienated from traditional scientific institutions and is eager for fundamental change, even if the proposed changes don’t directly address their immediate grievances.

The event’s organizers seem to understand that their strength lies not in intellectual coherence but in channeling widespread dissatisfaction into political momentum. By positioning themselves as champions of “ordinary Americans” against an out-of-touch scientific elite, they’ve created a movement that transcends traditional policy debates.

What emerged from the MAHA Institute gathering was not a blueprint for scientific reform but rather a political strategy that leverages scientific controversies for broader institutional change. The “second scientific revolution” appears less about specific methodological improvements and more about redistributing power within the scientific establishment—a goal that resonates deeply with an audience that feels marginalized by mainstream scientific discourse.

The implications extend beyond academic debates about research methodology. This movement represents a fundamental challenge to how scientific authority is established and maintained in American society, suggesting that the post-pandemic period may mark not just a moment of scientific reckoning but a broader political realignment around questions of expertise, authority, and who gets to determine truth in public health and medical research.

As Bhattacharya and his allies continue to push for institutional changes at the NIH and other scientific bodies, they’re doing so with the backing of a politically mobilized constituency that views the current scientific establishment not as a neutral arbiter of truth but as a partisan actor that needs to be fundamentally restructured. Whether this vision of a “second scientific revolution” will gain traction remains to be seen, but the MAHA Institute event demonstrated that the movement has already succeeded in creating a powerful political force demanding change.

Tags: MAHA Institute, second scientific revolution, Jay Bhattacharya, NIH reform, pandemic policies, scientific authority, replication crisis, alternative medicine, anti-establishment science, political mobilization, scientific methodology, COVID-19 skepticism, Anthony Fauci criticism, mainstream science distrust, Make America Healthy Again, scientific revolution, institutional reform, public health policy, research methodology, scientific consensus, alternative treatments, vaccine skepticism, scientific authority redistribution, political science movement, pandemic response criticism, scientific establishment overhaul, replication standards, publication metrics, ordinary Americans science, ecclesiastical authority comparison, biohazard neighbor concept, satirical pandemic film, Nature Science reporter exclusion, scientific truth democratization, constructive scientific disagreement, reproduction in science, scientific idea validation, pandemic anger fuel, intellectual coherence absence, politically potent coalition, scientific elite challenge, expertise authority questions, truth determination power, NIH institutional changes, politically mobilized constituency, neutral arbiter challenge, partisan scientific actor, fundamental restructuring demand

Viral Phrases: “second scientific revolution,” “replication revolution,” “ordinary Americans,” “high scientific authority,” “mere biohazards,” “ridiculous geniuses,” “democratized science,” “crisis of high scientific authority,” “truth-making power,” “constructive ways forward,” “egomaniacal lightweight,” “placebo vaccines,” “hostile review,” “weaponize science,” “scientific truth democratization,” “spiritual truth,” “scientific idea success,” “broad science,” “new ideas from disagreement,” “scientific elite,” “fundamental restructuring,” “politically potent constituency,” “intellectual disconnect,” “power redistribution,” “neutral arbiter challenge,” “partisan scientific actor,” “politically mobilized constituency,” “fundamental institutional change,” “scientific establishment overhaul,” “truth determination power,” “expertise authority questions,” “scientific authority redistribution”

,

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!