Why people can have Alzheimer’s-related brain damage but no symptoms

Title: Groundbreaking Studies Reveal How Some People Defy Alzheimer’s: The Secret to Brain Resilience

Subtitle: Scientists uncover surprising biological mechanisms that protect certain individuals from cognitive decline, even in the presence of Alzheimer’s hallmark proteins.

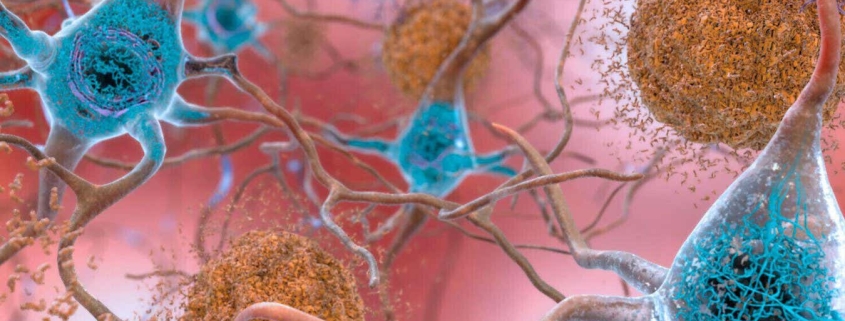

In a stunning breakthrough that could reshape our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease, two pioneering studies have illuminated why some individuals develop the characteristic brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s—amyloid plaques and tau tangles—yet remain cognitively sharp well into their 90s and beyond. This remarkable phenomenon, known as Alzheimer’s resilience, has long puzzled researchers, but new evidence suggests the brain possesses sophisticated defense mechanisms that shield certain people from the devastating cognitive decline typically associated with these pathological markers.

The Paradox of Resilient Brains

Alzheimer’s disease has traditionally been understood as a straightforward equation: the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and tau tangles in the brain leads to neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment. However, recent research reveals this relationship is far more complex than previously thought. Some individuals accumulate these pathological proteins yet maintain exceptional cognitive function, challenging our fundamental understanding of the disease mechanism.

Dr. Henne Holstege, leading a team at Amsterdam University Medical Center, has been at the forefront of investigating this paradox. Her research focuses on centenarians—individuals who have reached 100 years of age—many of whom show significant Alzheimer’s pathology in their brains at autopsy yet demonstrated remarkable cognitive preservation throughout their lives.

Centenarian Secrets: When Pathology Doesn’t Equal Decline

In a comprehensive analysis of 190 deceased individuals ranging from 50 to over 100 years old, Holstege’s team made a startling discovery. Among the centenarians studied, 18 individuals showed amyloid plaque levels comparable to those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, yet their tau tangle levels remained similar to healthy individuals who died decades earlier.

This finding suggests a crucial insight: while amyloid plaques may set the stage for Alzheimer’s progression, it is the accumulation—not merely the presence—of tau tangles that appears to drive cognitive symptoms. “Without amyloid, we don’t see tau spreading,” explains Holstege, highlighting the complex interplay between these two pathological proteins.

The research team’s protein analysis revealed another fascinating dimension to this puzzle. Among nearly 3,500 proteins examined in the brain tissue, only five showed significant associations with amyloid plaque abundance. In stark contrast, approximately 670 proteins correlated with tau tangle abundance. These tau-associated proteins play critical roles in cellular functions including growth, communication, and metabolism—particularly the breakdown of cellular waste products.

“Everything changes with tau,” Holstege emphasizes, underscoring the protein’s central role in Alzheimer’s pathology. This massive disruption of cellular processes may explain why tau accumulation proves so devastating to cognitive function.

The Critical Distinction: Spread vs. Accumulation

Perhaps the most revolutionary insight from Holstege’s research concerns how we understand tau pathology. The study revealed that among the 18 resilient centenarians with elevated amyloid plaques, 13 showed substantial tau spreading throughout the middle temporal gyrus—one of the first brain regions affected in Alzheimer’s disease. However, despite this widespread distribution, the overall amount of tau remained remarkably low.

This distinction between tau spreading and accumulation challenges current diagnostic approaches. Alzheimer’s disease is typically diagnosed based on the extent to which tau has spread throughout the brain, but these findings suggest that cognitive decline may depend more on tau buildup than its geographic distribution.

“We should really understand that spreading does not necessarily mean abundance,” Holstege explains. This insight could revolutionize how researchers approach Alzheimer’s diagnosis and treatment, shifting focus from preventing protein spread to controlling protein accumulation.

Microglia: The Brain’s Immune Guardians

The second groundbreaking study, led by Dr. Katherine Prater at the University of Washington, provides crucial insights into the cellular mechanisms underlying Alzheimer’s resilience. Analyzing the brains of 33 deceased individuals—including those with Alzheimer’s, those without it, and resilient individuals—Prater’s team discovered that resilient brains exhibit unique characteristics in their microglial cells.

Microglia are specialized immune cells in the brain that serve multiple critical functions: regulating inflammation, maintaining neuronal health, and clearing away cellular debris, including amyloid plaques and tau tangles. Previous research has shown that microglia become dysfunctional in Alzheimer’s disease, potentially contributing to neurodegeneration.

Genetic Clues to Resilience

Prater’s genetic analysis of microglia from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex—a brain region crucial for complex cognitive functions like planning, decision-making, and problem-solving—revealed striking differences between resilient individuals and those with Alzheimer’s. Microglia from resilient brains showed increased activity in genes involved with transporting messenger RNA, the genetic instructions for making proteins.

This enhanced mRNA transport capability suggests that microglial cells in resilient individuals are more efficient at delivering genetic instructions to where proteins are synthesized. This process, when disrupted, can be particularly detrimental to cellular health. “If that process gets interrupted, we know that is really bad for cells,” Prater notes.

Additionally, microglia from resilient individuals displayed decreased activity in genes involved with energy metabolism compared to those from Alzheimer’s patients. This lower metabolic activity mirrors patterns seen in healthy brains, suggesting that Alzheimer’s disease may be associated with increased microglial energy consumption, potentially due to heightened inflammatory activity.

Inflammation: The Hidden Culprit

The connection between microglial function and inflammation provides crucial insights into Alzheimer’s pathology. Brain inflammation is known to disrupt neuronal connections and contribute to cell death, but the exact mechanisms linking inflammation to cognitive decline have remained elusive.

Prater’s findings suggest that resilient individuals may possess microglial populations that are better equipped to manage inflammatory responses while maintaining their critical housekeeping functions. This balance between immune defense and cellular maintenance may be key to preventing the cascade of neurodegeneration that characterizes Alzheimer’s disease.

Implications for Treatment and Prevention

These groundbreaking studies offer more than just scientific curiosity—they point toward potential therapeutic strategies that could transform Alzheimer’s treatment. Rather than focusing solely on preventing amyloid plaque formation or tau tangle spread, researchers may need to develop approaches that enhance the brain’s natural resilience mechanisms.

“The human brain has ways of mitigating tau burden,” Prater observes. Understanding these natural defense mechanisms could lead to treatments that prevent Alzheimer’s altogether, rather than merely slowing its progression once symptoms appear.

The Path Forward

While these findings represent significant advances in our understanding of Alzheimer’s resilience, researchers emphasize that practical therapeutic applications remain in the future. “We are certainly not close to a therapeutic yet,” Prater cautions, “but I think that biology is showing us there is hope and there is promise.”

The research also raises intriguing questions about individual differences in Alzheimer’s resilience. What genetic factors contribute to these protective mechanisms? Can resilience be enhanced through lifestyle interventions or therapeutic approaches? How do environmental factors influence the brain’s ability to manage pathological proteins?

A New Era in Alzheimer’s Research

These studies mark a paradigm shift in Alzheimer’s research, moving beyond the simple accumulation of pathological proteins to explore the complex biological systems that determine whether those proteins cause harm. By understanding why some brains can harbor Alzheimer’s pathology without suffering cognitive decline, researchers may unlock new approaches to prevention and treatment that could benefit millions affected by this devastating disease.

The discovery of Alzheimer’s resilience reminds us that the human brain possesses remarkable adaptive capabilities that we are only beginning to understand. As research continues to unravel these protective mechanisms, the dream of preventing Alzheimer’s disease—rather than simply managing its symptoms—comes closer to reality.

Viral Tags: Alzheimer’s breakthrough, brain resilience secrets, centenarian cognitive health, tau protein mystery, microglial immune cells, preventing Alzheimer’s naturally, cognitive decline resistance, brain inflammation solutions, genetic Alzheimer’s protection, revolutionary dementia research

Viral Phrases: “Defying Alzheimer’s at 100,” “The tau accumulation paradox,” “Microglia: Brain’s hidden guardians,” “When plaques don’t equal decline,” “Nature’s Alzheimer’s shield,” “The resilience revolution,” “Breaking the Alzheimer’s equation,” “Brain’s built-in protection,” “The spreading vs. accumulation mystery,” “Hope in the pathology paradox”

,

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!