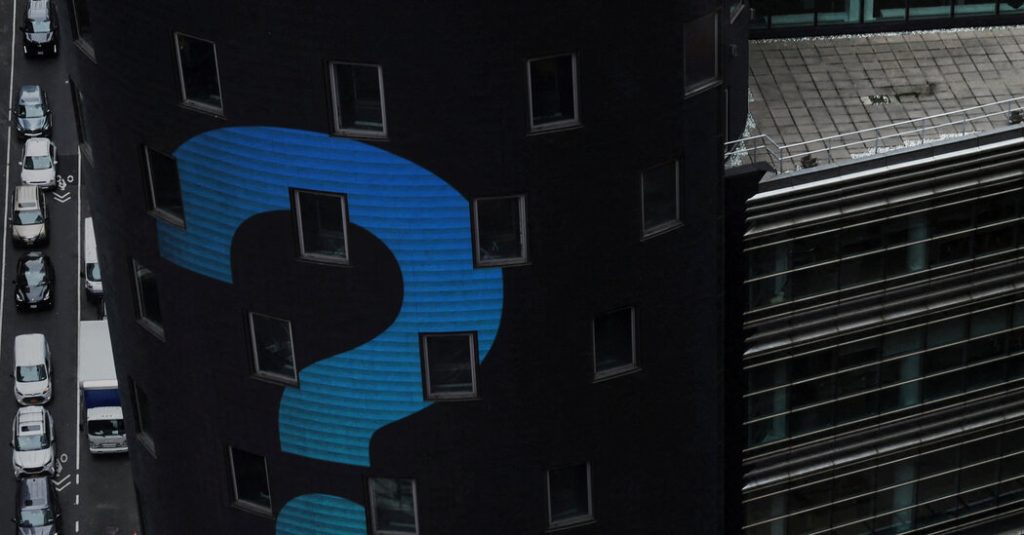

Here is a puzzle at the center of online life: How should we balance freedom of speech with the flood of slanderous statements, extremist manifestoes and conspiracy theories that proliferate on the internet? The United States decided decades ago to let private companies solve that quandary themselves. The Supreme Court made this position official in three major rulings in the 1990s and early 2000s.

But lawmakers aren’t sure about this arrangement, now that giant online platforms are the new town square. The left says Facebook, YouTube, TikTok and the rest should take more content down, especially hate speech and disinformation. The right says the companies, which removed posts about Covid and the 2020 election, shouldn’t set the rules for discussions about politics and culture.

Now a series of federal court cases will address these questions. Supreme Court justices will decide a few in the next month or two. In today’s newsletter, I’ll explain how those cases could change the way the First Amendment functions in the internet era.

The decisions

Courts have faced six broad questions about online speech. The Supreme Court has ruled on two of them.

-

When can social media sites be sued over what users post? Rarely. Two Supreme Court rulings last year kept protections in place for websites from most lawsuits related to content posted by users. Relatives of victims of terrorist attacks had argued that Google and Twitter should be legally responsible for content posted by the Islamic State. The justices disagreed.

-

Can government officials block constituents on social media? Sometimes. The Supreme Court ruled in March that public officials can’t stop a constituent from commenting on their posts if they are acting in their role as political officeholders.

The questions

Four other philosophical questions are still in progress.

-

Can the government force social media sites to host political content? Twitter, YouTube and Facebook suspended Donald Trump in 2021 after the Jan. 6 riot. Then Florida and Texas passed laws designed to restrict such moves. The Supreme Court will soon rule on those laws, and the justices appeared skeptical of them during oral arguments in February, my colleague Adam Liptak reported.

-

When can the United States push social media sites to remove content? The government prodded social media services to take down certain posts related to Covid and elections. Missouri, Louisiana and five individuals argued that’s a violation of the First Amendment. They say the government used private companies to stifle a specific viewpoint. The Supreme Court seemed wary of the lawsuit in March. The justices’ skepticism of conservatives’ argument is a sign of how complex it is to draw boundaries in this area of the law.

-

Can the government restrict access to online pornography? Texas passed a law last year that requires adult sites to check the age of their visitors. Parents can sue sites if the sites fail to do so and their child views pornography. If the law stands, adults will need to reveal their identity to pornography sites instead of remaining anonymous. The sites say this puts a barrier between adults and speech they have a right to view under the Constitution. The case is now in federal appeals court.

-

Can the government ban a foreign-owned social media platform? President Biden signed a law in April that will ban TikTok unless it is sold by its Chinese parent company, citing national security. TikTok says the measure curtails free speech rights — both its own and its users’. Federal courts are planning to hear the case this year. If they uphold the law, it will affirm the federal government’s right to eliminate a platform for speech in the national interest. If judges strike it down, it may allow news and social media sites to serve Americans even when they are owned by a company from an enemy nation.

What this means for users

With this many kinds of cases, the range of outcomes is vast. If the courts decide the status quo is wrong, internet platforms might limit what you can post — or take down more of it — just to be sure they are complying with the laws.

Another possibility: The courts could decide that they got this question right the first time they considered it, 30 years ago. Free speech online might not change much. But private companies would now formally be entrenched as its arbiter.

For more

-

Germany has gone further than any other Western democracy to prosecute right-wing extremists for what they say online, testing the limits of speech on the internet.

-

State lawmakers worked with Silicon Valley to write new measures that would protect children from online sexual exploitation. Then social media companies sued.

THE LATEST NEWS

Israel-Hamas War

Better friends: Want to strengthen your relationships? Join our 5-day friendship challenge.

Metropolitan Diary: He had a cameo in “Taxi Driver.”

Lives Lived: Jean-Philippe Allard was a French record executive and producer who helped revive the careers of jazz greats who had been all but forgotten in the U.S. He called himself a “professional listener” and developed lifelong relationships with artists he worked with. He died at 67.

SPORTS

Twenty-five years ago this summer, the author Thomas Harris released “Hannibal,” the long-awaited sequel to 1988’s “The Silence of the Lambs.” Critics praised the sequel, as had Stephen King. However, negative reviews started to appear on Amazon, which, in 1999, was emerging as a crucial feedback machine. Read a retrospective about the release of the book, which was among the last blockbuster novels of the 1990s and the first of hyper-opinionated internet era.

More on culture

#Internet #Amendment,

#Internet #Amendment